Checkpoint 10 at last. After two hundred forty kilometers, too-many-to-count meters of climbing, a third cold sleep-deprived night behind me, I felt desperately ready for another rest.

I could hear Brenda, my coach and crew leader, cheering us on, telling us to haul ass. Nothing unusual about that (Brenda is dangerous with a megaphone in her hand). But as my pacer Corinne and I came splashing through the cold water of Lost Creek, something seemed off. There was an unusual edge of seriousness and urgency in Brenda’s exhortations.

I had spent nearly four hours at the previous checkpoint in Crowsnest eating, changing clothes, getting my feet cleaned and massaged, sleeping a good hour and a half, eating some more. Now I was being hustled along. Eat this. Put this on. Hurry! Lawrence, my next pacer, was hovering anxiously nearby. I heard something about a cutoff at CP12, but it didn’t really register (I had not given a thought to cutoffs, other than than the need to finish the race by noon Friday).

As we ran off towards North Kootenay Pass, Lawrence gave it to me straight.

On paper, I wouldn’t make it. I had long since ditched my original plan, having fallen hopelessly behind after the third checkpoint. I would need to complete the next 37 kilometers roughly an hour faster than a planned pace I already wasn’t coming close to matching. So, yes, almost no chance.

But not no chance. Lawrence started explaining the math (Lawrence, I would learn, is man of many talents, one of which is a knack for doing calculations in his head). My foggy brain didn’t follow the details, but grasped the gist. I would have to give absolutely everything I had left over the next several hours, then maybe, just maybe, we would make it.

And there it was again. Sitting calmly in a corner of my brain. An absolute certainty that I would finish the race.

“Are you in?” Lawrence needed to hear me say it.

“I’m in.”

La Coulotte

Divide 200 begins with an almost ludicrously challenging, glorious first day. Before seeing their crew for the first time at CP3, racers must cover some 69 kilometers and 4100 meters or so of climbing, with a similar amount of descending.

The start of the race to the first checkpoint, a flat and fast warmup, saw me struggling with a minor tech malfunction. My Garmin InReach wouldn’t pair with the Explorer app on my phone, so if I wanted to send a text message, I had to painstakingly tap it out on the InReach interface. Nor did the device seem to be pairing with my saved Garmin Explorer maps. I flipped back and forth between Garmin Explorer and Gaia, flummoxed that nothing seemed to be working right, nearly tripping over roots a few times. Wanting to calm my mind, I decided to ignore the tech. As my smartwatch had never been turned on in the first place, for the rest of the race, I had little more than the time of day to guide me–for better and for worse, as it turned out.

There was a bit of a traffic jam coming into and out of the checkpoint, as racers filled their bottles and bladders for the long, waterless alpine stretch to come.

The day was glorious, clear skies and little wind, as we began our ascent to La Coulotte Ridge. As we made our way from lower elevations to subalpine, lodgepole pines and Douglas firs gave way to progressively shorter, windblown Engelmann spruce. As the trees thinned, views opened up of mountainsides of sedimentary rock, layers of sandstone, shale and limestone from ancient seas. There were vast reddish and orange mountainsides, interspersed with grey granite, gneiss and schist. Great amphitheaters carved out by glaciers, exposing loose plummeting slopes of scree.

My previous experiences of alpine landscapes had been brief passages between ascending and descending a mountain, but La Coulotte went high and stayed high for many hours. Sometimes described as the most rugged stretch of the Great Divide Trail, this route crosses multiple peaks, descending down loose scree slopes, climbing up boulder field after boulder field. Wayfinding would normally be difficult, but with an extraordinarily well flagged course and plenty of racers still about me during this first day, I had no navigational challenges.

One moment on La Coulotte haunts me. A reddish mountainside of broken stones loomed ahead. Through the boulders I could see a single runner, struggling up the side of the mountain on a trail I would soon be on as well. At once I felt a power residing in the mountain, a presence so palpable and real I came to a stop. I could hear the wind and my breath. I stood still for some time. Only when I started running again did I notice my eyes were full of tears. I have told few people about this. I consider myself a secular and rational person, and don’t know what the experience means.

Finally the descent off La Coulotte began. Now the landscape unrolled in the other direction, from alpine, to subalpine, to montane forest. As we descended, I listened intently for water. It had been 30 minutes since I had emptied my two and a half liters of water, and now I could feel the heat of the day, the dry air, the effort of running and hiking, all relentlessly pulling moisture from my body.

Getting a bit carried away, in the descent I tried to pass a few runners who were walking–and hit an embedded rock, coming down hard and leading with my chin, which came away with a bit of a gash that probably looked worse than it felt. Chins bleed, a lot.

At last we came to a spring, bubbling out of the mountainside. There were several runners gathered at the source, filling their bottles. If I could give my past self some advice, it would be to stop at this spot a bit longer, drink more, rather than immediately filling up and pushing on. Pennywise and pound foolish I was at this early stage of the race. Small actions have big ripples in a race this long.

Through the long afternoon and the dwindling light I ran towards the next ascent, up to Whistler and Table Mountains. This was a 15 km mostly flat stretch through the forest. I still had plenty of company at this point, and ran or power hiked with several Edmonton friends who were also in the race.

I was on my own when I started the ascent up Whistler, which would make, by itself, a challenging day of climbing, but in the context of this day was just another mountain to get up and over. I don’t recall much about the ascent. My head was down and I was working my way methodically upwards. Things were still going well. Mostly. Until I reached the summit.

Descent in the Dark

Small actions have wide ripples: my decision to ignore tech issues and my decision to downplay dehydration had consequences.

Covering the 10 kilometers of trail linking Whistler and Table Mountains–and in gathering darkness, as it turned out–required a fair bit of wayfinding. I kept switching back and forth from the Gaia app to Garmin Explorer, trying to find the most helpful signal, but just confused myself and wasted time in the process. Meanwhile, the wind and cool of evening reminded me I needed to get off the mountain.

The sense of relief, when I finally found myself on the descent down Table Mountain, was short lived. This is a technical, sometimes wet and treacherous descent that would be challenging enough during the day. At night, it was especially so (not helped by the cataract in my right eye). I was getting sleepy now, and probably not eating enough, with nausea–perhaps a product of my earlier dehydration–gradually creeping up on me.

I heard voices: a group of three runners travelling together. I waited for them, thinking it better to descend Table Mountain with others than alone. It was one of those encounters in the dark where you don’t see anyone’s faces, but piece together personalities through conversation. The young woman who led our little group was one of those people (I would meet several during the race) who had run multiple 200s. She shared how the first day of Divide was harder than anything she had experienced at other 200s.

The group of us stopped periodically to wait for one of the runners (not me, not yet) who was feeling queasy. Very queasy, apparently, because we heard her puking behind us. Her vomiting seemed to flip a switch in my brain. My own queasiness became steadily stronger with every step down the mountain. I knew better than to continue on with an empty stomach…but that’s exactly what I did, drinking a little, then less, eating a token amount now and then, just trying to get through to Checkpoint 3 where (magical thinking!) everything would be made right.

Hallucinating with eyes wide open

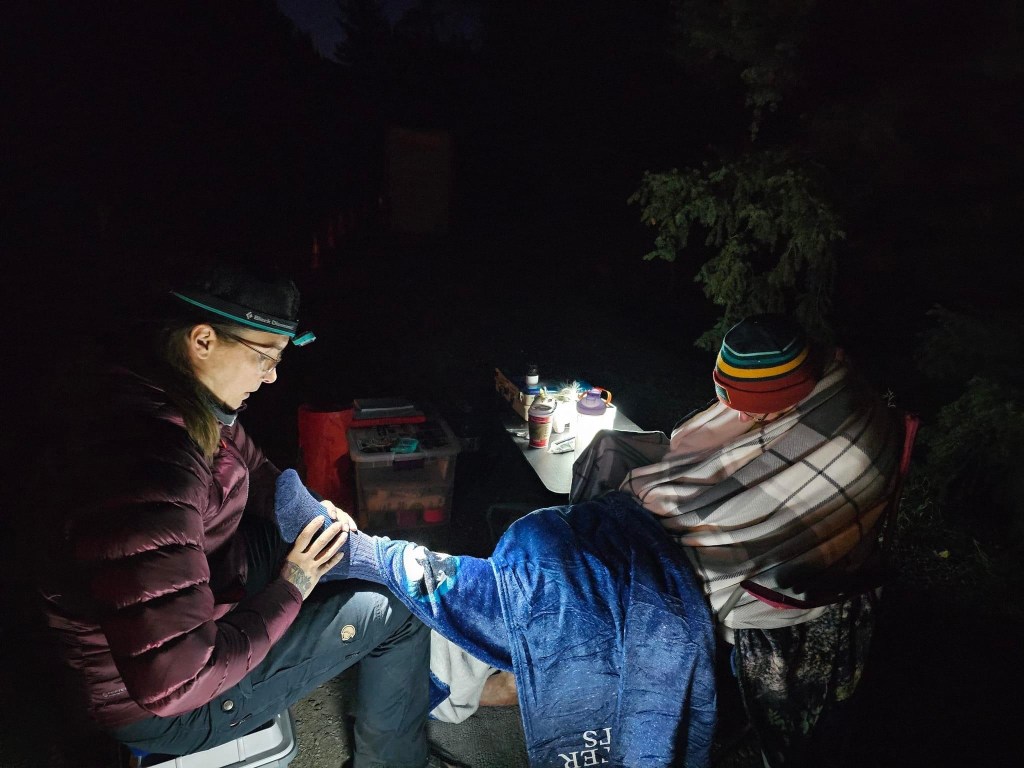

Checkpoint 3 is the first time racers have a chance to see their crew, and after 69 kilometers and some 4100 plus meters of climbing, it is a welcome sight. Many things were indeed put to right in Checkpoint 3, where Brenda quickly took control, wrapping me in the “burrito blanket” which was to become something of a signature look for me in the race.

She quickly ran down the list of questions for me, and in my foggy mental state I did my best to answer. The cut and bruise on my chin–no big deal. Leg muscles: surprisingly good, with really minimal quad soreness considering the thousands of meters of descending.

Drinking and eating: not so good. I had started the day well enough, but had trailed off somewhere between Whistler and Table Mountains, and now was in a nutritional and hydration hole, unable to hold down food, nauseous from a lack of calories (the most common cause of nausea in an ultra), yet because of this, also limited in my ability to take in more.

Brenda had me take in a little apple sauce; then, armed with the instruction to take in small amounts every ten minutes or so, I was sent out into the night to take on CP3 to CP4–what should have been an easy, relatively flat 21 kilometers, leading through the forest and back to Castle Mountain Resort.

It was not easy. About 2 kilometers in, I puked. That set the stage for the next several hours, which is how long it took me to cover this modest, unchallenging distance. I mostly walked through that night, sucked down apple sauce, waited to see how that settled, and slowly progressed through the forest.

Then the hallucinations began. Yes, the first night, and my subconscious was acting out. Forest undergrowth became coffee tables, random kitchen appliances (sometimes wrapped in plastic!), and of course, I saw the obligatory bear log. In the hour before dawn, the visions escalated a bit. I saw a figure standing by the side of the trail, handing out pamphlets. I did not take one.

The rising sun made everything better. My head cleared, my stomach improved, and I was able to run the last bit into Checkpoint 4. This was another crewed checkpoint, another opportunity for recuperation and refueling. Brenda’s notes say that I took in 2 pancakes, some hashbrowns, then headed for the sleep station where, despite the light, I got a good half hour or forty-five minutes (eyemask and earplugs were, for me, a must at sleep stations). After sleeping, I ate some more, filling my pockets with pancakes and hashbrowns in ziplock bags (“breakfast pockets” as Brenda says), then headed out for the long trail to Crowsnest.

It was a strange, solitary sort of day–and one that would shift my mental state, helping me to find a calm corner of my mind where I knew, whatever the evidence to the contrary, that I would finish the race.

For the 18 or so kilometers to Lynx Creek, I rolled over some minor hills, including a rare segment of road running. The roads were mostly deserted. The sky was clear, the sun up, and the temperature continuing to rise, balanced by a cooling breeze. I was running again, even the uphill sections, and feeling pretty good, making steady if not fast progress.

Coming into the bare-bones Checkpoint 5, I refilled my water, grabbed some hummus and pita bread, and headed for the shade of a tree, where I lay in the grass, ate, and stared at puffy clouds in the blue sky. I felt at peace, and could happily have slept.

Time to push on, however. I made my way up the ascent and back to the Continental Divide Trail. I reflected how the 920 meters of climb that would seem like a big mountain day in regular life now seemed a modest climb. Up onto Willoughby Ridge there were some spectacular views of surrounding peaks, but given the height, nothing in the way of a creek or spring to restock my water. Fortunately, I had taken on board plenty of water at the last checkpoint. I was feeling rather pleased with myself (usually prelude to a mistake). One hundred kilometers in, and I was doing alright, still moving well enough, and even passing a few stragglers over the past few hours.

A few hallucinations lingered from the night, holding on even in the bright light of day. Now they took the form of what looked like lettering inscribed in stones–secret messages, naturally meant just for me. On closer inspection, the secret runes dissolved into random lichen patterns, cracks in stone.

I felt oddly detached, calm, a sympathetic observer alongside my body rather than a self that suffered. In Buddhism, there is a story the Buddha tells of the “two arrows.” The first arrow is the pain that life inevitably flings our way. The second arrow is the suffering we inflict on ourselves, the ways we magnify pain through stories, explanations, ruminations.

Somewhere in that 26 kilometer segment, the second arrow was sheathed for me, and would remain permanently sheathed for the remainder of the race.

This peculiar state of mind almost derailed my race–until it saved my race. Over the next day I would be untroubled by the urgent InReach messages from Brenda to “pick up the pace.” I gave no thought to how many hours I was falling behind my plan. I gave no thought to how, checkpoint by checkpoint, the distance between my time and cutoffs was narrowing. With hallucinatory clarity, I had no doubt I would complete the race.

CP 6 to CP 9: the Epic Window Mountain Loop

It is difficult to choose a favorite section of Divide, but if I had to, this would be it. The sheer beauty of Window Mountain Lake in all its autumnal glory would be enough. But for me, what made this most enjoyable was the company.

The solitary running of the previous 135 kilometers was over, and my pacer for this epic section would be Brennan, who kept me entertained (and moving forward) for the next 66 kilometers and 2413 meters of climbing. Pacers in this race have to be as well-trained, self-sufficient, and mountain-ready as racers. Any one of the sections where pacers are allowed would be, in itself, a significant challenge. The challenge for Brennan, a seriously fast ultramarathoner, was a bit different. With the ability to podium in the race (which I believe he will one of these days), he had to endure what must have felt like my excruciatingly slow progress. The entire 66 kilometers, he was full of energy, ready to run up and down the mountains. A high-spirited young mountain goat stuck with a tired old pack mule for a traveling companion.

I had come into Checkpoint 6 as darkness fell on the second night. My stomach was good, and I was eating–though still not enough, according to Brenda. I explained that I would eat more but–and here, I was so muddle-headed I couldn’t remember the word “saliva”–I didn’t have enough “mouth water.”

After more eating, I made my way to the sleep station, bringing the burrito blanket with me. Then followed a fitful 45 minutes in which I don’t think I slept at all. The sleep station at CP6 was adjacent to a tent full of people talking and blaring music, and I was surrounded by tired runners restlessly tossing and turning. Not at all refreshed, I came out of the tent, changed to warmer clothes, and, to Brenda’s satisfaction, downed some veggie broth and yet more breakfast.

Brennan and I headed out into the second night. The cold was manageable; we were well dressed. That night, deep in the forest, my hallucinations blossomed, the most fantastic and persistent they would be for the entire race.

I would see entire houses now, where there was nothing but trees before. For someone with little drawing ability, my subconscious conjured a remarkable amount architectural detail. Some houses had wraparound decks, with bicycles, barbecues, and windchimes. Some were more like cottages, moss-covered walls, flowerboxes below shuttered windows. There were driveways, sometimes well-lit, with parked cars, SUVs and sedans. In one especially strange moment I saw Brennan standing in a non-existent driveway, next to a non-existent open door. It seemed odd that he couldn’t sense any of this. As I came closer, the driveway dissolved into forest floor, the open door revealed itself as a faintly illuminated space between the trees.

The worst, as was the case every night, came just before the dawn. Somewhere out on Racehorce Pass and a seemingly endless climb, I became seriously unmoored. Now, I might turn a corner, and an entire imaginary neighborhood would spring up out of the trees. I could see Brennan ahead, feel the poles in my hand, hear the clicking of the poles on the trail–but none of this made any sense. It was not nonsensical in an existential “why am I putting myself through this” sort of way–but literally nonsensical. I could not think what I was doing, what the poles were for, why I was the woods. As my brain fumbled about, I thought vaguely that there must be some sort of complex financial or logistical calculation I had to solve, an overstretched budget to balance, a plan to devise.

These periods of dreaming while awake gave way, almost as suddenly, to sharp clarity, moments in which I knew exactly what was happening. Finally, the sky began lightening. The clarity grew in my mind to a steady awareness and alertness. The trees were, at last, simply trees.

While we had dressed well for the cold night, we hadn’t given much thought to the heat of the day. The trail to Window Mountain, and indeed for much of that day, was exposed and increasingly warm. I had forgotten sunscreen, and had a warm toque but no cap.

Nonetheless, I feel fortunate to have been just slow enough to experience this stretch in the daytime rather than at night. The mountain itself is stunning. The glacier-carved lake was a dreamy turquoise, and all up the side of the scree slope there was a trail winding through multi-coloured underbrush, reddish-purple Spiraaea and red-twig dogwood. Above us loomed the great amphitheatre of Window Mountain, so named because of a limestone arch, or window, near the summit.

Passing beyond the lake, we entered a rolling and open landscape, gradually descending. Highrock Trail on the way to CP 8 was glorious but now seriously hot in the exposed sun. We stopped under isolated clumps of trees and removed the last of our overnight warm clothing, including a pair of tights that I had kept on for far too long.

What should have been an uneventful final stretch back to Crowsnest became a misadventure, as (and not for the last time) we became lost and turned about in the branching trails by a stream. After running in frustrating circles for several extra kilometers, we at last found our way to CP8 and so, from there, slowly but steadily back to town.

Crowsnest to CP 10

Once again, I was running into C6, now CP9, as the sun went down. After that epic loop, I was truly exhausted, and famished. The cold of night was already gathering. I was quickly wrapped in the burrito blanket and handed a plate of felafel, which I polished off with barely a pause. My feet were surprisingly good, with not a single blister (I think I had one blister in the entire race). I had hot spots on both Achilles, however, which Brenda fixed with KT blister tape–a solution which turned out later to work perfectly. After eating, drinking, and getting my feet tended to, I hobbled off to the sleep station. This time the station was quiet, dark, and with my eye mask and ear plugs in place, I quickly blacked out. I was allowed to sleep a whole hour and a half, my longest sleep, and sorely needed.

After sleeping there was – more eating. Brenda had heard from a 200 mile crew veteran that those who survived these races made use of the aid stations to down huge amounts of food–1200 or more calories at once. Lawrence showed up with an A&W Beyond Burger and root beer which I polished off immediately. Hands down, this was the best meal I’ve ever eaten My body was desperately craving protein and fat and took it all in gratefully.

Altogether, I was in the checkpoint about three and half hours, a long stop but necessary. Although I wasn’t conscious of it, however, I was drawing ever closer to the cutoff time.

Corinne joined me for the night run out of town, on the trail south to Castle Wildlands and Lost Creek. We ran through the neighborhoods out of town, and promptly got lost, looping back a couple of times on ourselves, and probably adding a few kilometers, before getting on track. I was not particularly worried, though, and was happy to follow Corinne’s light bobbing up and down in front of me. She tells me that I told her she looked like a UFO; I don’t remember saying this, but it sounds about right.

We made slow progress up the trail, sometimes along a range road, walking as much as running through the night. We received a message at one point that we were off track, and puzzled over the map for awhile. The challenge of these sorts of messages was that there is often a delayed effect with the InReach signals: you might have been off track a half hour before anyone would notice. Stephen (who would eventually time out before CP11) passed us up, and we tried to catch up, finally doing so and running together for a good part of the ensuing segment. As always, it was the period before dawn that was the worst. A couple of times I had to pull over, close my eyes, and half-nap, even if just for a moment.

At one point, Corinne thought she saw a cougar in the path up ahead. We approached slowly and saw…a large ptarmigan.

At last, the sun was up, and we were making our way to Lost Creek and the end of this seemingly endless segment.

The Race to Checkpoint 12

It was already quite warm as Lawrence and I set off for North Kootenay Pass and Checkpoint 11, on the BC side of the Divide. We ran along a wooded trail, paralleling the Carbondale River, through lush forests of lodgepole pine and Douglas Fir. Having learned the lesson of the previous day, I had sunscreen on, my light cap, plenty of water in my pack.

Lawrence tried to convey to me that my race was now on a knife’s edge, on the wrong side of the edge most likely. As the path started to switchback up, the terrain gradually shifted, trees thinning out, the odd open meadow tinged with fall colours. Lawrence was the ideal leader: periodically tell me my pace (too slow, pick it up), tell me to eat or drink, mixing tough love with encouragement in perfect proportions.

He put up with my ridiculous arguments. Still feeling a bit sleepy, even in the bright sun, I told Lawrence that Brenda had said I could take a dirt nap at the top of Kootenay Pass (I have no idea whether this is true). He gave me a skeptical look. “Maybe,” he said, “we’ll see when we get there.”

It was during the climb to the North Kootenay Passthat my hiccupping began. The hiccups morphed into uncomfortable, then actually painful, diaphragm spasms so persistent that I had to stop every ten or fifteen minutes, unable to breath and gasping for air. The spasm would pass, and I’d be able to run again–until the next moment of crisis.

This pattern of pain would continue for the next five or six hours.

Finally we were toiling up the last, steepest section to the top of the pass, which comes into view as a distant notch in a long serrated ledge, baking in the hot wind, treeless, rocky, an ascent up Mt. Doom. The sun was seemingly right over the notch, so we hiked into the wind and into the blinding light. The footing became looser, shards of scree crunching underfoot. Gusts of wind sent sand skittering across the bare ridges.

My diaphragm spasms seemed to get worse the higher we went. When the fit came–like clockwork, it seemed–I would lean on both poles, bent over, gasping. When I could breath again, I’d immediately begin pushing upwards again. And like clockwork, Lawrence would be there, reminding me to take another gel, keep drinking.

At the top at last, I took a moment to lean on a boulder in the shade, sheltering a brief moment from the wind. It was clear there would be no dirt nap. I didn’t need to ask. Lawrence stared unhappily at his watch. We weren’t making good enough progress. We would have to run the downslope and trail to CP11 “all out.”

The initial descent westward went through my least favorite terrain: steep, rocky, fragmented, with shattered, uncertain footing plunging down into the forest. Lawrence led the way. He’s one of those guys who wears minimalist shoes and flies over the most technical terrain, dancing from one precariously moving rock to another. I’m the opposite. I did my best, though, to imitate him, trying to relax, trying not seize up with fear as with seemingly every step the earth moved sideways.

Eventually the terrain smoothed out, the descent became milder, and we were truly running now over the rolling hills towards CP 11. My diaphragm spasms continued, forcing me to stop periodically, but I kept up the pace, matching Lawrence’s stride, running faster than I had at any point in the race.

We flew through CP11, stopping only for a very quick water fill. The two women volunteering at this remote checkpoint were fantastic, cheering and encouraging us as we took off at a run. (I would see them again, and have a chance to thank them, at the finish.)

There were about two hours remaining to cover the distance to CP 12 before the cutoff. We were still on the wrong side of the cutoff, but gaining momentum, on track to cover the section hours faster than my original ETA. The diaphragm spasms were acute now, seemingly worse the faster we ran. We picked up the pace. I argued a bit with Lawrence over taking in fuel, which I thought was exacerbating the the spasms–but he insisted, rightly, knowing that by this point in the race, any stored glycogen I might have would be minimal. He didn’t want me bonking before we reached CP12.

As we got closer to the checkpoint, race crew drove to and fro a couple of times. They were heading further back, to check on racers still on the course–runners who were not going to make the cutoff. They encouraged us, however, saying we were going to make it, we were on track, and not to worry if we were a few minutes over the cutoff. That last part encouraged me most. It was the first time the rational part of my brain and the magical thinking part were in alignment: we might actually pull this off.

Several kilometers away still from CP12, we could see, at the top of the next rise, a person standing on the road. She seemed to be looking for something off the side of the road, and was wandering vaguely from bush to bush, moving slowly along the road ahead of us. I couldn’t tell what she was doing, and thought at first it was a volunteer from the Checkpoint, perhaps keeping a lookout for runners. But as we got closer, I could see the woman was a runner, with a pack and a number.

What we learned later from Selina was that she was so loopy and so out of it that she had been searching for a place to take a nap. Nap! So close to the checkpoint, and so close to the cutoff, she thought only of sleep. I could relate to that.

As we caught up to her, there were just a few kilometers left, and now Lawrence urged us both onward. The last mile was pretty much all out–our miracle mile, Selina called it later. Cresting the final hill, we could at last hear the cheers–real cheers, not the hallucinatory ones I heard earlier, that turned out to be the wind sighing through the trees. Brenda was standing in the middle of the road, and others were coming out of the checkpoint to watch. When I reached her, my legs buckled, and she helped me towards the chair and aid stations. I was well and truly done.

Finale – the road home

I was in Checkpoint 12 for all of seven minutes. I was puzzled at first, as everyone seemed sad and hushed. My race belongings were packed into little bags surrounding my feet. Brenda was saying something about my race being over, and was reading Facebook posts in a consolatory way to suggest it had been a great effort.

I heard the words, but sort of smiled inwardly, thinking: why is everyone worried? What is this talk about dropping? I am going to finish.

Then several things began happening at once. People started bustling around, and I heard someone say “five minutes!” “Can you have them out of there in five minutes!” As I learned later, there were behind the scenes frantic calls to Brian, the Race Director, urging him to allow Selina and me to continue, although we were several minutes (seven, I think) over the cutoff. Perhaps the crew and volunteers had been inspired by our desperate push to CP12; in any case, they really went to bat for us. All I knew at the moment was that I had to grab my gear, some bags of warm weather clothing and additional food, and hobble the 150 meters over to the other side of a little bridge, just outside the magic circle of the aid station.

According to the rules, once outside a Checkpoint, no crew member or volunteer can offer aid to racers. Racers and their pacers could support each other, but no one else could do more than offer encouragement and moral support. Lawrence, Selina and I parked ourselves on the side of the road. Brenda was now joined by Corinne and Brennan, who had originally been slated to take over pacing duties for the final 46 km stretch of the race, but had arrived a few minutes too late. More behind-the-scenes drama I was unaware of at the time: crews face some daunting logistical challenges in this race, and none more so than getting to the extremely remote Checkpoint 12. Without hesitation, Lawrence agreed to another 46 km, adding to the 37 km he had already travelled with me.

Now outside the bounds of the checkpoint, I lay down in the dirt and fell at once into a dreamless sleep.

Coming to a half hour later, it was time to put our warm clothes for the night that was already beginning to gather around us. There was more than a marathon distance to go, and another pass over the Continental Divide to navigate, but we no longer had any worries about time. I had a night and a morning to get back to Castle Mountain Resort.

It was a long night. Colder, it seemed, than any of the previous nights–though this may just have been a result of moving more slowly and sheer exhaustion. All I could do in the dark was power hike–and barely that. The diaphragm spasms had stopped entirely with the slower pace. I no longer fought Lawrence on his reminders to eat, and I kept a reasonable flow of calories going through the long night. The most challenging aspect of this stretch from CP12 to CP13 was my intense desire for sleep. More than anything, my only wish was to stop moving, to sleep. I hiked along behind Lawrence, weaving from side to side. When my waywardness became too extreme, and he saw I was about walk off the road entirely, we finally stopped for a dirt nap, one of a few I took along this stretch. Climbing into my emergency bivvy sack (surprisingly effective for so light and flimsy a piece of kit), I had a glimpse of the Milky Way, impossibly dense with stars, before everything went dark.

Arriving in Checkpoint 13, I was still desperate to sleep, and while Selina and Lawrence chatted with race crew around a fire, I crawled off to a corner of the shelter. I was offered a piece of cardboard to sleep on. I loved that piece of cardboard! It seemed like an incredible luxury after the rocks and dirt of my roadside sleeping spots.

The final section was golden. The trail goes for about 18 kilometers or so, with a roughly 600 meter climb up the South Kootenay Pass. Where the North pass had seemed like a trial by fire, this was a manageable climb into the gently warming air of morning. South Kootenay is, and felt, quite remote. There is no road access to this area. The three of us made our way up through the boulder fields and scree slopes, ascending at the top to alpine terrain, a litter of glacially carved stones and a fantastic view down into Alberta and the headwater areas of the Oldman River.

Lawrence urged us on, told us we should push for time, but Selina and I were of one mind in wanting to savor this section. While Lawrence darted ahead, dancing from stone to stone in the rock strewn eastern descent (Selina said he looked like a bee) the two of us ran, tentatively, managing the descent in measured but steady progress. We talked for a bit about who would finish last, each politely suggesting the other could go ahead, until we hatched our plan to finish together, hand in hand, ensuring there would be two winners of the Red Lantern Award.

Further down, we made our way on to the game trails and streambeds, coming at last into the subalpine forest and the trails that would take us to the finish. The countryside began to look familiar, and we debated whether we had run this section on the first day, four days earlier. Then, coming into view of the Castle Lodge, Selina and I put our plan into place: we crossed the finish line with hands clasped overhead. As we crossed, there was confetti or party streamers in the air–courtesy, I think, of Selina’s daughter.

Aftermath

The recovery from an effort like this differs for every runner. Some finishers suffered swollen feet, others a variety of aches and pains. The week after for me brought surprisingly little soreness, and no pain. My digestive system was a mess, and I found my usual diet (wholefoods, high fiber, vegan) far too challenging at first, sticking to toast and processed food. The worst, however, was the persistent fatigue–like being hit by the flu. I rather foolishly tried to work this week, thinking working from home would not be too taxing. Instead, I found that after every video meeting I had to crawl back to the sofa and nap. The afternoons seemed to drag on forever. I wondered how I ever made it through normal workdays.

Sleeping was little relief, however, as every night for that first week, I dreamt only about running: I was perpetually on the trail, running, moving forward through wild terrain. I awoke feeling exhausted, and with a sense that that I needed to get going, needed to be somewhere.

One day after about a week, I finally dreamt about something other than running. I was strolling up a snow covered path. There were others with me, but for some dream-logic reason, I had to take this path alone.

As I shone my light on the path, I could see there were bear tracks in the snow, disappearing into a forest. I felt a surge of fear, and was about to turn back. Then, in the way of dreams, I understood the bear wasn’t stalking me: it was leading me. I awoke feeling refreshed, the fatigue gone. My Divide adventure at last was over.

Leave a comment